<link href="https://cdn.sur.ly/widget-awards/css/surly-badges.min.css" rel="stylesheet">

<div id="surly-badge" class="surly__id_56779743 surly-badge_white-gradient" onclick="if(event.target.nodeName.toLowerCase() != 'a' && event.target.parentElement.nodeName.toLowerCase() != 'a') {window.open('https://sur.ly/i/parentingwithouttears.com/'); return 0;}">

<div class="surly-badge__header">

<h3 class="surly-badge__header-title">Content Safety</h3>

<p class="surly-badge__header-text">HERO</p>

</div>

<div class="surly-badge__tag">

<a class="surly-badge__tag-text" href="https://sur.ly/i/parentingwithouttears.com/"> parentingwithouttears.com </a>

</div>

<div class="surly-badge__footer"> <h3 class="surly-badge__footer-title">Trustworthy</h3> <p class="surly-badge__footer-text">Approved by <a href="https://sur.ly" class="surly-badge__footer-link">Sur.ly</a> </p> </div> <div class="surly-badge__date">2023</div>

</div>

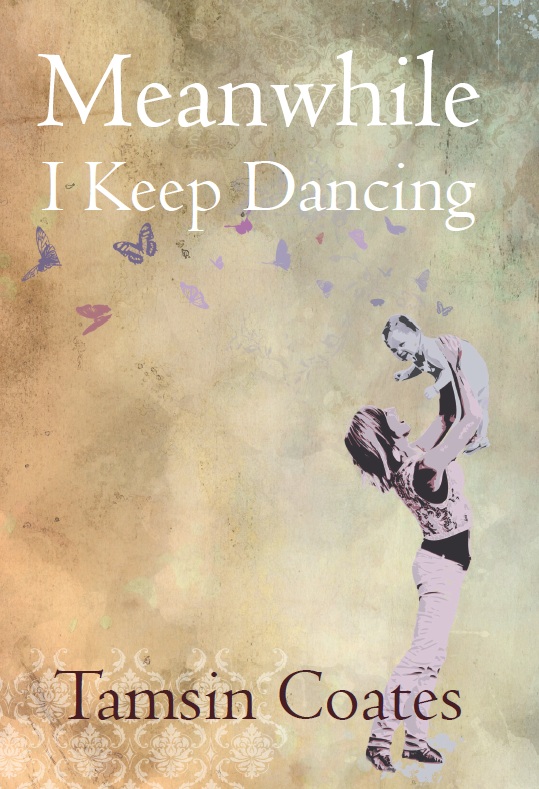

Tamsin Coates, the author of Meanwhile I Keep Dancing, is a Speech and Language Therapist whose two sons were diagnosed early on as deaf – a diagnosis that came out of the blue, with - obviously – a huge emotional impact on both parents. She explains how it all started with one child’s suspected “glue ear”, a commonplace enough problem. Tests when one son was 18 months old and the other only three months led to hearing aids but a “crossroads” decision was to follow when it became evident that hearing aids didn’t work for the younger son: should he have the operation to fit a cochlear implant?

Tamsin Coates, the author of Meanwhile I Keep Dancing, is a Speech and Language Therapist whose two sons were diagnosed early on as deaf – a diagnosis that came out of the blue, with - obviously – a huge emotional impact on both parents. She explains how it all started with one child’s suspected “glue ear”, a commonplace enough problem. Tests when one son was 18 months old and the other only three months led to hearing aids but a “crossroads” decision was to follow when it became evident that hearing aids didn’t work for the younger son: should he have the operation to fit a cochlear implant?